Interview with Elisabeth Benard by Sarah Fleming June 05, 2022

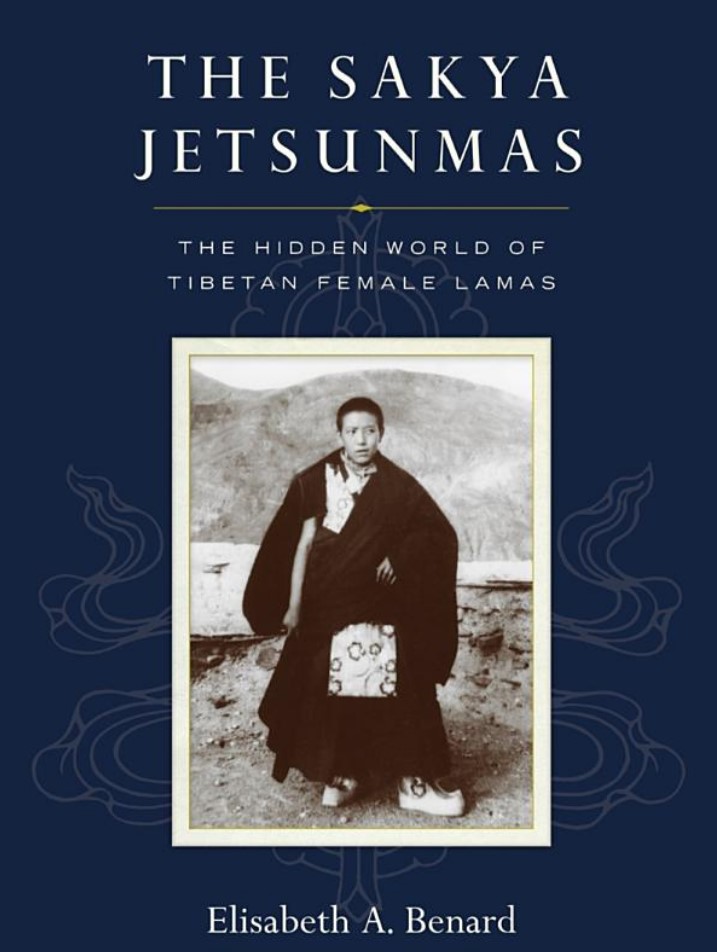

Jetsun Kushok at nineteen years old, Dolma Palace, Sakya, Tibet, 1957

For over a thousand years, the Sakya Khon family has trained both its sons and daughters as great spiritual teachers. Though many of the men within the Khon family are well known, the stories of female adepts are rarely shared. Known as jetsunmas (venerable women), these women begin studying Tibetan at the age of six and train with the highest lamas of their time. They have played a pivotal role in the development of the Sakya tradition within Tibetan Buddhism, and yet they often remain nameless in historical accounts of the Khon family lineage.

In the new book The Sakya Jetsunmas: The Hidden World of Tibetan Female Lamas, scholar Elisabeth Benard brings the stories of these women to light. This multigenerational collection of biographies is the first book written in English about the Sakya jetsunmas, and it draws extensively from archival research, oral histories, and interviews with living members of the Khon family.

Tricycle sat down with Benard to discuss the extraordinary lives of these women, including two contemporary jetsunmas who are still practicing today; how the jetsunmas have grappled with histories of persecution and exile; and how they’re shaping the future of the tradition.

What is a jetsunma, and how does someone receive the title?

Jetsunma is the feminine form of the word jetsun, and it means “one worthy of worship” or “venerable woman.” There are very few women who have this title, and there are two ways to receive it: either someone is born into a particular family and is given the title at birth, or a community or a lama recognizes them as a great practitioner and confers the title. The second case is more common, as there are only a couple families that pass on the title at birth, the Sakya Khon family and the Nyingma Mindroling Trichen family.

Can you share a little about the Sakya Khon family and what’s unique about the Sakya jetsunmas?

The Sakyas are a spiritual family that began in the 11th century in a place in Tibet that is now known a Sakya. Sakya literally means “pale earth,” as the earth in the area is noted for its pale gray color. The founder of the Sakya school, Khon Konchok Gyalpo (1034–1102), had a vision that he had to build a temple on Sakya’s pale earth, so he decided to build Sakya Monastery. When the great Indian pandita Atisha first saw the land of Sakya, he prophesied that there would be emanations of the different bodhisattvas of compassion, wisdom, and power born there. This all coalesced in the Sakya Khon family. Indeed, many of the male members of the Khon family are considered to be bodhisattvas, either of compassion, wisdom, power, or a combination of all three. The jetsunmas, on the other hand, are usually considered to be emanations of the goddesses Tara and Vajrayogini. What is unique about the Sakya family is that they’re committed to train both their sons and their daughters to become great religious practitioners and, if they have the abilities and the interest, to become great lamas.

What does that training process look like?

Since the Khon family has existed for 1,000 years, they’ve developed a detailed process of training. Jetsunmas begin studying as children, learning to read Tibetan texts at the age of five or six. They are given empowerments (in Tibetan, wang), and these empowerments serve as an introduction to a specific deity. Each deity is usually considered to have one particular quality. The child is then instructed to do a daily practice where they concentrate on developing and nurturing the deity’s quality in themselves. A lama will watch the child to see how his or her practice is going, and when the lama feels that the child is ready, they’ll start to receive much more extensive teachings and commentary. Some of these teachings can take days. The lama will also pass on the more experiential parts of the teachings, which are only shared in private settings. After a child receives these teachings, then they go on a retreat to know the deity more fully. The lengths of these retreats can vary. One of the most important deities in the Sakya tradition is Hevajra, and becoming familiar with Hevajra takes seven to eight months of solitary retreat. Not everybody receives every empowerment—it all depends on each person and what they’re interested in or what the lama thinks is good for them.

What is unique about the Sakya family is that they’re committed to train both their sons and their daughters to become great religious practitioners.

In writing this book, you had the chance to interview Jetsun Kushok, a jetsunma who is still teaching today. Can you share more about her training process in particular?

Jetsun Kushok was born in 1938 on the holy day of Lhabab Duchen, the date when the Buddha descended from Tushita Heaven after visiting his mother to share the Abhidharma teachings. To be born on such a day was considered a sign that Jetsun Kushok would most likely be a very good teacher. As a child, Jetsun Kushok dealt with a lot of tragedy. Her mother was in frail health, so Jetsun Kushok was raised by her aunt, Dagmo Trinlei Paljor, who was a great practitioner. In the next few years, her mother gave birth to a son and a daughter, both of whom passed away in childhood. In 1945, her mother gave birth to another son, who would become the 41st Sakya Trizin, or throne holder of the Sakya school. Shortly thereafter, she passed away. But despite losing her mother and two siblings, Jetsun Kushok was not alone—she had very strong role models to follow, including her maternal aunts, who were all practitioners. She trained intensively with her aunts and was given many responsibilities at a young age.

In 1949, when Jetsun Kushok was 11 years old, the great temple in Sakya was hit by lightning. Her father was asked for money to fund the repair. The Dolma Palace didn’t have enough money on hand, so Jetsun Kushok’s father sent her to the nomadic regions north of Lhasa to collect donations. She embarked on the trip with her aunt, her teacher, a cook, three horsemen, and six monks. As an 11-year-old, she was in charge of performing all the rituals. She traveled for six months giving long-life empowerments and collecting donations, and she ended up gathering over 1,000 dotse (the highest denomination of the currency at that time), in addition to a number of animals and other gifts that she had to sell before returning to Sakya. She didn’t waste any money whatsoever, as she felt that it was her responsibility and duty to serve her father and the Sakya community.

One night during that trip, she was staying at a small monastery, and there was a knock on her door. Some monks had arrived and were determined to get a divination from her. Among Tibetan lamas, divinations are quite common. The most common method is through throwing and interpreting dice, which requires a lot of training since you have to be able to rely on specific deities to guide you through the process.

The monks asked her to do a divination about their abbot. Their abbot had supported the former regent, who had died mysteriously after being arrested for plotting to assassinate the current regent. They were very worried about what would happen to their abbot and feared the worst. And so in the middle of the night, Jetsun Kushok got up to throw the dice for them. Based on her interpretation, she recommended that they recite the Praises to the Twenty-One Taras 100,000 times. The monks left early in the morning, and Jetsun Kushok forgot all about the experience. But two years later, in 1951, while she was in Lhasa with her family, the same group of monks requested an audience with her. They thanked her profusely and shared that their abbot was released the day after they had completed the 100,000th recitation of the Praises to the Twenty-One Taras. The monks attributed their abbot’s freedom to the divination she had done as an 11-year-old.

Jetsun Kushok praying to Tara at the Mahabodhi Temple,

Bodhgaya, India, 2002. Photo by April Dolkar

Shortly after that, the Chinese government invaded Tibet. How did persecution and exile impact Jetsun Kushok and the Sakya family?

In 1959, when the Communist Chinese Army invaded Tibet and the Dalai Lama fled the country, many other Tibetans followed suit, including the Sakya family. In order not to draw the attention of the Chinese government, they had to be very secretive, and only a very small group could escape. Jetsun Kushok was able to leave with Sakya Trizin and their aunt, first to Sikkim and then to India. They were living as refugees, and they didn’t have very much money. Since Sakya Trizin was the throne holder of the Sakyas, he received a lot of attention, and everybody wanted to help him develop and train properly. But Jetsun Kushok was not given that kind of attention.

In the beginning, she still dressed in her nun robes and kept her head shaved. But in India, the only women who had shaved heads at the time were widows, and widows were considered highly inauspicious. When Indian people saw her, they treated her like a widow. Eventually, she decided to disrobe because it was just too difficult. After she disrobed, sometimes Tibetans would still recognize her and try to make prostrations to her. But she was conflicted because she felt she wasn’t dressed properly for such signs of respect. It was no longer clear who she was or what was expected of her.

How did she navigate life in India after disrobing?

While her brother was receiving many teachings from eminent lamas, Jetsun Kushok’s future in India was less clear. She briefly served as a nurse, caring for sick children, before the unclean conditions made her sick. Eventually, Jetsun Kushok’s aunt, Dagmo Trinlei Paljor, decided that she should marry. This was unusual because jetsunmas are nuns and take vows never to marry. At first, Jetsun Kushok protested and wanted to remain a nun, but eventually she acquiesced. Her aunt found her a suitable partner from a prestigious family, Sey Kushok Rinchen Luding, and they married. They’re still together to this day, and it has turned out to be a fantastic relationship. They soon had their first son, and over time their family grew to include five children. After training and teaching as a jetsunma for so long, Jetsun Kushok now had to learn how to manage a household, balancing children on her hips while doing laundry and chores.

After a few years, a friend suggested that the family immigrate to Canada. But when they arrived in Canada, they had no support at all. In India, she had been with her immediate family in the birthplace of the Buddha. But in Canada, nobody knew about Tibet or the Khon family. They were simply new immigrants. Both Jetsun Kushok and her husband had to find jobs, and they ended up working on a mushroom farm, filling and transporting 20-pound boxes of mushrooms. It was back-breaking work. They had never really done physical labor before, and they would come home each day exhausted.

Still, she always found time for her practice, waking up at 4am and reciting mantras while doing her house duties.

Eventually, Jetsun Kushok returned to teaching. How did that happen?

In the 1970s, Sakya Trizin came to the United States to teach. Some of the female students asked him, “Why is it that in Tibetan Buddhism all the teachers are men? Where are the female lamas?” Sakya Trizin told them that there were women teachers too, including his elder sister, who was living in Canada. The women were very interested to know that there was a female lama so nearby, so Sakya Trizin asked Jetsun Kushok to teach. She began giving empowerments and instructions at Sakya Trizin’s centers in the US and became well known in many parts of the world. To this day, I think she’s probably one of the most important living female lamas that we have. But she likes to keep a very low profile, which is why not many know too much about her—or about the Sakya family in general. When I received the Sakya family’s support to write this book, I found it quite extraordinary because this is the first time that Jetsun Kushok’s biography will be shared with a larger audience.

In the epilogue of the book, you share the story of another contemporary jetsunma, Jetsunma Kunga Trinley Palter, born in 2007. Can you share more about her life and how the jetsunma training process has changed in the 21st century?

Jetsunma Kunga Trinley is the granddaughter of Jetsun Kushok’s brother, the 41st Sakya Trizin. She is the first jetsunma who is also a recognized reincarnation, or tulku—she was recognized by the Dalai Lama as the reincarnation of Khandro Tare Lhamo. She is also the first jetsunma to be brought up in India and educated both in the traditional Sakya manner and through a modern education. She has received empowerments from her grandfather, her father, and other lamas, and in many ways, she is being trained just as if she were a jetsunma in Sakya. At the same time, she’s also attending a small private school in Dehradun, in Northern India, where she is learning the standard subjects that most children learn today. She seems to have a proficiency for languages: she already knows Tibetan, Hindi, Chinese, and English. Because she is growing up in the 21st century, we have greater access to what her training process has looked like: her parents documented her early life online through a photographic journal, and important moments in her life continue to be shared on Facebook and YouTube.

Jetsunma Kunga Trinley is a path blazer in many ways. Besides being the first jetsunma to be recognized as a tulku, she is also the first vegan jetsunma, as she ate only vegetarian foods from birth and cut out animal products altogether at a very young age to minimize harm and show compassion toward sentient beings. In addition, she is the first jetsunma to have learned the Vajrakilaya sacred dance. For all the sons in the Sakya family, learning this dance is a rite of passage, and other people interpret their connection to the deity of Vajrakilaya based on the way they perform the dance. Before Jetsunma Kunga Trinley, no woman had ever performed this dance. She committed to training herself, and she performed the dance just last year. I believe that she has opened the doors for her sisters and other Sakya nuns to be able to perform the dance in the future. Just in her first 15 years, she has set so many “firsts” and has shown herself to be deeply involved in the dharma. She is well on her way to becoming an esteemed lama—and paving the way for other jetsunmas to follow. After over 1,000 years, the Khon family is thriving.

Sarah Fleming is Tricycle‘s audio editor.

Elisabeth Benard previously worked as a professor of religion at the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Washington. Since her retirement, she has continued to pursue her interest in goddesses and spiritual women, compiling biographies of hidden yoginis in Tibetan Buddhism.