[et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default”][et_pb_row _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default”][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default” text_font=”|600|||||||” header_font=”|600|||||||” header_text_align=”center”]

In Memoriam – Thich Nhat Hanh

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][et_pb_row column_structure=”1_2,1_2″ _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default”][et_pb_column type=”1_2″ _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default”][et_pb_image src=”https://www.inebnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/thay-stupa.jpg” title_text=”thay stupa” align=”center” _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default”][/et_pb_image][/et_pb_column][et_pb_column type=”1_2″ _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default”][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default”]

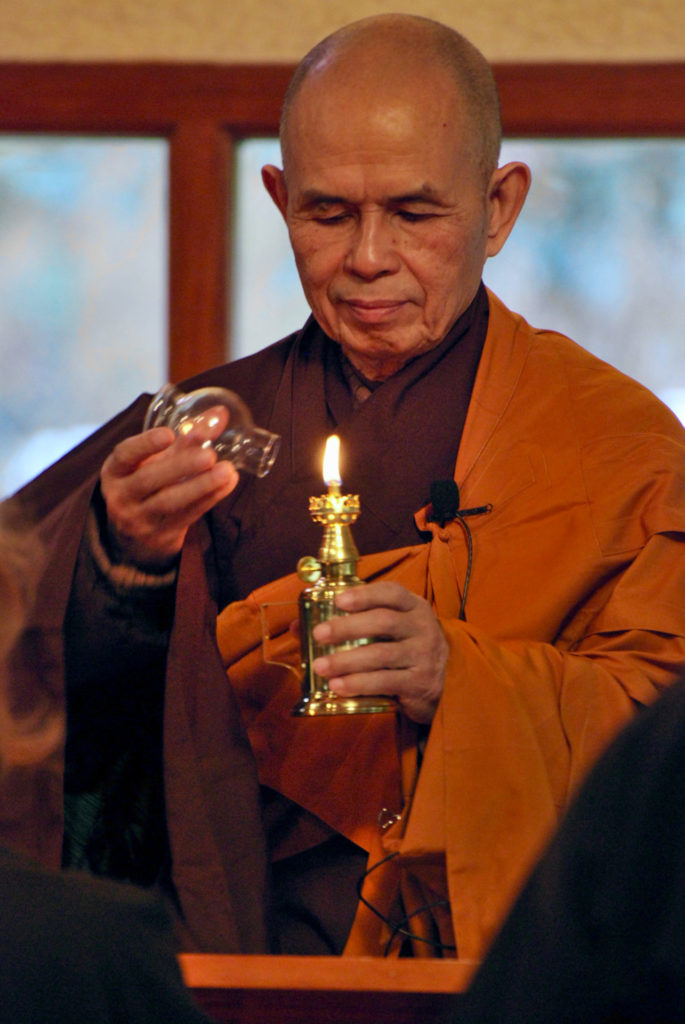

On January 22nd, 2022, beloved Vietnamese Zen Master and pioneer of Socially Engaged Buddhism Ven. Thich Nhat Hahn passed away peacefully at Tui Hieu Temple in Hue, Vietnam.

Since their first meeting in 1975, Thich Nhat Hanh’s inspirational synthesis of Buddhist practice and social action has exercised a profound influence on Sulak Sivaraksa’s vision of a Socially Engaged Buddhism – ultimately leading to INEB’s founding in 1989 and Thay’s 33 years of supportive patronage.

May his passing serve to remind us of compassion’s immeasurable strength as we continue to walk the path of service, one peaceful step at a time.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][et_pb_row _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default”][et_pb_video_slider _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default”][et_pb_video_slider_item src=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d7gOL61cR6o” _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default” show_image_overlay=”off”][/et_pb_video_slider_item][/et_pb_video_slider][et_pb_video _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default” src=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ooPJS3b6GzY” hover_enabled=”0″ sticky_enabled=”0″][/et_pb_video][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][et_pb_row _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default”][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default”]

Please click on a name below to view commemorations:

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_accordion admin_label=”Accordion” _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default” scroll_fade_enable=”on” motion_trigger_start=”top”][et_pb_accordion_item title=”His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama” open=”on” _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default” link_option_url_new_window=”on”]

I am saddened to learn that my friend and spiritual brother Venerable Thich Nhat Hanh has died. I offer my condolences to his followers in Vietnam and around the world.

In his peaceful opposition to the Vietnam war, his support for Martin Luther King and most of all his dedication to sharing with others not only how mindfulness and compassion contribute to inner peace, but also how individuals cultivating peace of mind contributes to genuine world peace, the Venerable lived a truly meaningful life.

I have no doubt the best way we can pay tribute to him is to continue his work to promote peace in the world.

[/et_pb_accordion_item][et_pb_accordion_item title=”Ajahn Sulak Sivaraksa” _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default” open=”off”]

Thich Nhat Hahn—My Friend and My Teacher

The Vietnamese Zen Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh—my friend and my teacher—died on January 22, 2022. Thay (meaning “teacher”) lived an extraordinary life of socially engaged Buddhism. The Dalai Lama recently wrote that the best way we can pay tribute to Thay is to continue his work to promote peace in the world. I agree and thought that I would take this opportunity to reflect on the Thay’s life.

Thay was born Nguyen Xuan Bao in Hue on Oct. 11, 1926. He joined a Zen monastery as a novice monk at 16. Upon his full ordination in 1949, he assumed the Dharma name Thich Nhat Hanh. Thich is an honorary family name used by Vietnamese monks and nuns. Thay’s study of the Buddha’s teachings coincided with political upheaval in Vietnam and eventually war that started in 1955.

Thay went to the United States in 1961 to study at Princeton and soon was appointed a lecturer in Buddhism at Columbia University. In 1963, he returned to Vietnam and continued to organize monks and laypeople in nonviolent peace efforts. He established schools for activists, including the Van Hanh Buddhist University in Saigon; founded the La Boi Publishing House; and wrote essays, books, and poems in several languages, inspiring a generation of peace advocates.

In 1964 Thay wrote published a poem called “Condemnation” in a Buddhist weekly, that in part read:

Whoever is listening, be my witness:

I cannot accept this war.

I never could I never will.

I must say this a thousand times before I am killed.

I am like the bird who dies for the sake of its mate,

dripping blood from its broken beak and crying out:

“Beware! Turn around and face your real enemies

— ambition, violence hatred and greed.”

Thay was labeled an “antiwar poet,” and he was denounced as a pro-Communist propagandist.

As Thay traveled in the US and Europe in 1966 with a mission to call for the end to hostilities in Vietnam, he met Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who the following year nominated Thay for the Nobel Peace Prize, saying, “Thich Nhat Hanh’s ideas for peace, if applied, would build a monument to ecumenism, to world brotherhood, to humanity.” Thomas Merton, after meeting Thay at Gethsemani Abbey in Kentucky in 1966, described him as “my brother” because of their common views.

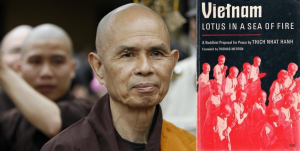

Thay published in 1967 a highly personal book about the war, “Vietnam: Lotus in a Sea of Fire”, which narrates his journey of transforming his religious beliefs into social action and his commitment to nonviolent conflict resolution. It was in this book that he articulated “engaged Buddhism,” a notion that greatly influenced Buddhist thinkers in Asia, including myself, and inspired spiritually inclined activists in the West.

An accomplished Buddhist scholar, Thay was fluent in Vietnamese, French, English, and Mandarin. He wrote in a way that transcends religious dogma and attracts readers of all faiths. In his work he places great importance on being “aware of the suffering created by fanaticism and intolerance” and is determined not to be “idolatrous about or bound to any doctrine, theory, or ideology, even Buddhist ones.”

“Our own life must be our message,” he often says.

While still in America in 1967, Thay received messages from Buddhist leaders in Vietnam telling him not to return lest he be imprisoned or assassinated. Thay then began a life in exile that would last thirty-nine years.

I first met Thay in Colombo, Sri Lanka, in 1974, at an interfaith dialogue that the World Council of Churches had organized for Hindu, Buddhist, Jewish, Christian, and Muslim social activists. The group took an excursion to pay respects to a famous relic of the Buddha in Kandy, and were received at the temple by Sri Lanka’s highest Buddhist dignitary, the Sangha Maha Nayaka. Thay had brought along a statement he had drafted in opposition to the Vietnam War, hoping to collect signatures in support of it. Because of the long history of close relationship between Thai and Sri Lankan Buddhists, Thay asked me to present the statement to the Sangha Maha Nayaka and request his endorsement. But the elderly Sinhalese monk told us, “No, I won’t sign this. I don’t want to be like the Dalai Lama and lose my country. Monks shouldn’t be involved in politics.”

Despite this disappointment, the occasion caused a mutual respect and camaraderie to arise between me and Thay. Our friendship continued as we both increased our social activism—my own in Southeast Asia, and Thay working the halls of power in the US and France to promote peace in Vietnam.

In 1975, I invited Thay to a three-week seminar I was organizing in northern Thailand, supported by the Quakers. Young people from various Southeast Asian countries came together in Chiang Mai to study nonviolence, to explore the power of the written word, to meditate and pray, and to spend time with senior activists like myself, Thay, and Swami Agnivesh from India. While the seeds of our friendship had been sown in Sri Lanka, it was on a mountain above Chiang Mai that our kalyana-mitta, spiritual friendship, blossomed. I watched Thay teach the young activists through his eloquent poetry and his gentle presence. Thay shared some of his writings—a manual for young meditators—that had been collected into a draft entitled “The Miracle of Being Awake.” I witnessed the powerful effect Thay’s writing had on everyone, including myself, and I decided to publish it for the first time in English in Thailand. The title was later changed to “The Miracle of Mindfulness”, which went on to become a worldwide best-seller, translated into more than thirty languages.

Thay’s articulation of Buddhist activism arose in the context of war. He coined the English phrase “engaged Buddhism,” which emerged from his writings in Vietnamese that stressed “renewing Buddhism” and “a Buddhism updated” (the translated title of Thay’s 1965 book Dao Phat Hien Dai Hoa), concepts that he combined with the French phrase le bouddhisme engagé. While many academics and activists have since tried to define what engaged Buddhism is, Thay is clear that what the Buddha taught more than 2,500 years ago was an ideal of acting within society, not withdrawing from it. The Buddhist path is by definition engaged with people because it deals with the suffering we encounter in ourselves and in others, right here and right now. I tend to use the term “socially engaged Buddhism,” a phrase that was spread widely by Parallax Press’s publications in the 1980s and ’90s and by the Buddhist Peace Fellowship newsletter in America (which today has evolved into Turning Wheel Media).

After the end of the Vietnam War, Thay could still not return to his country. He was not welcomed in Vietnam by the U.S.-backed government in the 1960s and early 1970s and then not by the Communists, who ruled the country ever since – both were afraid of Thay’s activism and anti-war stance. From his home in exile in Paris, Thay worked tirelessly to help his people. We assisted him in raising money through Bread for the World, the Asian Cultural Forum on Development, and other organizations, to ship rice into Vietnam in the mid-1970s, to help the fleeing boat people, and to facilitate adoptions of Vietnamese orphans.

In October 1976, I too was exiled from my home country during the bloody coup in Bangkok. I took the opportunity to stay with Thay in a small apartment in Paris and we also visited a small farm outside the city that he named the Sweet Potato Community. The community later moved to southwestern France and established Plum Village, one of the West’s largest Buddhist monasteries, with hundreds of resident monks and nuns, and where thousands of people from all over come annually to study Thay’s teachings on mindfulness and meditation. He later established monastic communities in Germany, Hong Kong, Thailand, and the United States, as well as meditation centers around the world, gaining an ever-growing global following.

I have fond memories of staying with Thay in his one-room apartment in France. When I would awake in the morning, Thay was already seated upright in meditation, well before dawn. Thay was showing me, by way of example the disciplined life of a meditator. After I roused myself, Thay taught me mindfulness of breathing and other meditation techniques. Although I had learned meditation as a novice monk, I had not cultivated the practice afterward. Such quiet periods, and long sessions of drinking tea with minimal conversation, were uncommon in my life of constant action. These weeks of meditation with Thay were joyful. When I experience strong emotions like anger, I always practice what Thay taught me so many years ago.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Thay rose to worldwide prominence as a poet, author, and meditation teacher, with many meditation centers to manage. Sometimes when we would meet during these years, in the spirt of kalyana-mitta, I expressed concern that Thay’s organization was getting too large and losing the spirit of socially engaged Buddhism. Thay always listened to my concerns. Matteo Pistono’s book “Roar: Sulak Sivaraksa and the Path of Socially Engaged Buddhism” delves deeply into my spiritual friendship with Thay.

In 2005 and 2007, Thay was allowed to return to Vietnam to teach and publish books, tour the country, and meet with members of his Buddhist order. His highly publicized visits created controversy among some Vietnamese Buddhist activists who criticized Thay for failing to speak out against the current governments alleged human rights abuses and poor record on religious freedom.

In 2013, Thay came to Thailand to visit a newly established Thai Plum Village International Practice Center outside Bangkok. We reminisced about our forty-year friendship, drank tea, and meditated. Thay gifted me an ink calligraphy that he painted of a Zen circle (enso) around the phrase “You are, therefore, I am.” I meditate upon this bodhisattva-inspired phrase regularly.

That was the last time I saw Thay as he suffered a severe stroke in November of 2014. He was unable to speak after the stroke but could communicate through gestures. Thay received expert medical care and support from Plum Village and eventually returned to his home in the Tu Hieu Temple in Hue, Vietnam, and that is where he passed away at the age of 95.

Thay wrote and taught often about death and dying, and in his book, No Death, No Fear, he concludes:

“This body is not me; I am not caught in this body, I am life without boundaries, I have never been born and I have never died. Over there the wide ocean and the sky with many galaxies All manifests from the basis of consciousness. Since beginningless time I have always been free. Birth and death are only a door through which we go in and out. Birth and death are only a game of hide-and-seek. So smile to me and take my hand and wave good-bye. Tomorrow we shall meet again or even before. We shall always be meeting again at the true source, always meeting again on the myriad paths of life.”

Source: Buddhist Door Global – https://www.buddhistdoor.net/news/sulak-sivaraksa-thich-nhat-hanh-my-friend-and-my-teacher/

[/et_pb_accordion_item][et_pb_accordion_item title=”Ven. Pomnyun Sunim” _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default” open=”off”]

Honorary Advisor, International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB)

[/et_pb_accordion_item][et_pb_accordion_item title=”Hozan Alan Senauke” _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default” link_option_url=”https://www.clearviewproject.org/2022/01/thich-nhat-hanh1926-2022-buddhist-revolutionary/?fbclid=IwAR2WZEPigPFnv5v_UNPG3Nhb_jR65EncNS3LpzjpZIBvPeS3JTILGysToP4″ link_option_url_new_window=”on” open=”off”]

January 22, 2022 – Thich Nhat Hanh always wore the simple brown robes of a monk. He walked and spoke mindfully as a Zen teacher, poet, and bridge between the world’s faiths. But the strength of steel lay just below his placid surface. It made him a kind of Buddhist revolutionary.

I recall Zen teacher Richard Baker’s description of Thich Nhat Hanh as “a cross between a cloud, a snail, and piece of heavy machinery—a true religious presence.” Now at the age of ninety-five, he has left this earthly plane and his frail body. But his wisdom and influence are strong, completely alive and essential.

When I started working at the Buddhist Peace Fellowship in the early 1990s, there was a broadside hanging over my desk with an excerpt from Thich Nhat Hanh’s book Peace Is Every Step. In part it read:

Mindfulness must be engaged. Once there is seeing, there must be acting. Otherwise, what is the use of seeing? We must be aware of the real problems of the world. Then, with mindfulness, we will know what to do and what not to do to be of help. … Are you planting seeds of joy and peace? I try to do that with every step. Peace is every step. Shall we continue the journey?

The disarmingly straightforward wisdom of Thich Nhat Hanh—more familiarly known to his students as Thay, meaning master or teacher—was tempered in Vietnam’s anti-colonial struggle against the French and the devastation of the U.S. war that followed. In the face of these conflicts, Thich Nhat Hanh brought a nonviolent movement to the Buddhist monasteries and created the School of Youth for Social Service, a cohort of Buddhist peace workers working in rural villages of Vietnam. “So many of our villages were being bombed,” Thich Nhat Hanh said:

Along with my monastic brothers and sisters, I had to decide what to do. Should we continue to practice in our monasteries, or should we leave the meditation halls in order to help the people who were suffering under the bombs? After careful reflection, we decided to do both—to go out and help people and to do so in mindfulness. We called it ‘Engaged Buddhism.’

In the late 1960s Thich Nhat Hanh was exiled from Vietnam—an exile that continued until 2005. Mistrusted by both the communists and nationalists in his own country, he steered a middle way of Buddhist-based nonviolence. In the U.S. he found like-minded comrades in Martin Luther King, Jr., Thomas Merton, the radical Catholic Berrigan brothers, western Buddhist teachers and students, and activists within the nonviolent circle of the Fellowship of Reconciliation and Buddhist Peace Fellowship.

I began reading Thay’s books in the 1980s, starting with The Miracle of Mindfulness and then Being Peace, the first Parallax Press book. After Being Peace, the stream of published words by Thay became a wide river, with brilliant commentaries on classic Theravada and Mahayana sutras, radical re-interpretations of the bodhisattva precepts, and Buddhist social commentary on our troubled modern world. As they rolled off the presses, his books were eagerly read by so many of us in the Buddhist community.

At the heart of his teachings Thich Nhat Hanh has driven home the centrality of mindfulness as the core of Buddhist practice. It’s fair to say that the flowering of our pervasive contemporary mindfulness “movement” has grown from the words of Thich Nhat Hanh.

As director of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship through the 1990s, I was asked by Thay and his growing community to organize biennial talks at the Berkeley Community Theater, which accommodated four thousand people. The first talk I organized was in April of 1991 in the immediate aftermath of Desert Storm, the first U.S. war against Saddam Hussein’s Iraq following its invasion of Kuwait, and the police beating of African-American Rodney King in Los Angeles.

I was struck by Thay’s comments that night. He spoke of his deep anger over the war in Kuwait and the beating of King, both of which seemed to trigger for him painful memories of the war in Vietnam and the brutal ignorance of U.S. oppression. He said he had considered cancelling his tour, with all its retreats and dharma events.

His words revealed to me that he wasn’t an unreachable saint, but a man with raw feelings. Then he shared that he’d meditated on his own reactivity and realized that he had to continue his tour as planned, because these oppressors and victims—the police, Rodney King, U.S. soldiers, Iraqis, and all their government leaders—were neither different from nor distant from himself.

That same week, in a Los Angeles Times op-ed, Thich Nhat Hanh wrote:

Looking more deeply, I was able to see that the policemen who were beating Rodney King were also myself. Why were they doing that? Because our society is full of hatred and violence. Everything is like a bomb ready to explode, and we are part of that bomb. We are co-responsible for that bomb. That is why I saw myself as the policemen beating the driver. We all are these policemen.

This insight about interdependence is what I have learned from Thich Nhat Hanh. It has infused how he has taught and walked in the world, but it is not a special vision of his own. Such insight appears to Buddhist and spiritual teachers of all lands and ages. It comes from poets and seers. Walt Whitman wrote: “I am large, I contain multitudes.”

Let us strive to be like Thay, that is, let us strive to be truly human, our true selves.

– Hozan Alan Senauke

Source: Clear View Project – https://www.clearviewproject.org/2022/01/thich-nhat-hanh1926-2022-buddhist-revolutionary/

[/et_pb_accordion_item][et_pb_accordion_item title=”The Monks and Nuns of Plum Village, France ” _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default” link_option_url=”https://plumvillage.org/about/thich-nhat-hanh/thich-nhat-hanhs-health/thich-nhat-hanh-11-11-1926-01-22-2022/” link_option_url_new_window=”on” open=”off”]

With a deep mindful breath, we announce the passing of our beloved teacher, Thay Nhat Hanh, at 00:00hrs on January 22, 2022 at Từ Hiếu Temple in Huế, Vietnam, at the age of 95.

Thay has been the most extraordinary teacher, whose peace, tender compassion, and bright wisdom has touched the lives of millions. Whether we have encountered him on retreats, at public talks, or through his books and online teachings–or simply through the story of his incredible life–we can see that Thay has been a true bodhisattva, an immense force for peace and healing in the world. Thay has been a revolutionary, a renewer of Buddhism, never diluting and always digging deep into the roots of Buddhism to bring out its authentic radiance.

Thay has opened up a beautiful path of Engaged and Applied Buddhism for all of us: the path of the Five Mindfulness Trainings and the Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings of the Order of Interbeing. As Thay would say, “Because we have seen the path, we have nothing more to fear.” We know our direction in life, we know what to do, and what not to do to relieve suffering in ourselves, in others, and in the world; and we know the art of stopping, looking deeply, and generating true joy and happiness.

Now is a moment to come back to our mindful breathing and walking, to generate the energy of peace, compassion, and gratitude to offer our beloved Teacher. It is a moment to take refuge in our spiritual friends, our local sanghas and community, and each other.

With love, trust, and togetherness,

The Monks and Nuns of Plum Village, France

[/et_pb_accordion_item][et_pb_accordion_item title=”INEB Secretariat ” _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default” open=”off”]

Celebrating the Life of Thich Nhat Hanh

The International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB) would like to take this occasion of the great passing of Vietnamese Master Thich Nhat Hanh to celebrate his life. “Thay,” as he was commonly called, has been our inspirational friend and revered patron throughout the years since INEB’s founding in 1989. His inestimable contributions before this time to a vision of modern Buddhism in the world, known as Socially Engaged Buddhism, were an integral reason that INEB could form and prosper as it has today. His passing has opened a time of deep reflection and contemplation amongst us about not only what it means to be socially engaged as Buddhists but more deeply about the very essence of our Buddhist practice.

In No Death, No Fear, Thay teaches us, as always, in a simple but deep prose that:

This body is not me; I am not caught in this body,

I am life without boundaries,

I have never been born and I have never died.

Over there the wide ocean and the sky with many galaxies

All manifests from the basis of consciousness.

Since beginningless time I have always been free.

Birth and death are only a door through which we go in and out.

Birth and death are only a game of hide-and-seek.

So smile to me and take my hand and wave good-bye,

Tomorrow we shall meet again or even before,

We shall always be meeting again at the true source,

Always meeting again on the myriad paths of life.

In this way, we understand that Thay continues on and that anytime we attempt to realize peace in the world by touching the peace within ourselves, he remains alive and close to us.

We offer these last lines of poetry from Please Call Me By My True Names written during the Vietnam War as “a bell of mindfulness” in the coming days when we reflect and also mourn on his leaving this physical realm:

Don’t say that I will depart tomorrow—

even today I am still arriving.

I still arrive, in order to laugh and to cry,

to fear and to hope.

The rhythm of my heart is the birth and death

of all that is alive.

Please call me by my true names,

so I can wake up

and the door of my heart

could be left open,

the door of compassion.

[/et_pb_accordion_item][et_pb_accordion_item title=”Matteo Pistono” _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default” open=”off”]

Peace Activist Poet, Thich Nhat Hahn, Dies

January 21, 2022 – Matteo Pistono (pistono@gmail.com)

The Vietnamese Zen Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh died January 15, 2022 at the age of 95 at his home in the Tu Hieu Temple in Hue, Vietnam. Nhat Hanh was a teacher, prolific writer and poet, and an advocate of socially engaged Buddhism.

His monastic organization, Plum Village, announced the death. Nhat Hanh had suffered a severe brain hemorrhage in 2014 in France and was unable to speak, though he eventually was able to communicate through gesturing.

Nhat Hanh was one of the most influential spiritual leaders in the world. He wrote dozens of books on mindfulness and peace, and sold over three million copies in the United States alone. Oprah Winfrey hosted him on her televised “Super Soul Sunday”, and on his last visit to the US in 2013, the tonsured monk led high-profile teaching and meditation events at The World Bank, Google, and the Harvard School of Medicine.

Engaged Buddhism

As a monk in the 1960s, Nhat Hanh was a leader in the revitalization of Buddhism in Vietnam. His highly personal book about the war in his country, Vietnam: Lotus in a Sea of Fire, published by progressive Christians in the US, narrates his journey of transforming his religious beliefs into social action and promotion of non-violent solutions to conflict. It was in that book where he articulated, “social engaged Buddhism,” which influenced greatly contemporary Buddhist thinkers in Asia, and inspired spiritually inclined activist in the West.

Though an accomplished Buddhist scholar, fluent in Pali and Sanskrit, Nhat Hanh’s writings and teachings were marked by his ability to transcend religious dogma. He placed great importance on being “aware of the suffering created by fanaticism and intolerance, [and not to be] idolatrous about or bound to any doctrine, theory, or ideology, even Buddhist ones.”

“Our own life must be our message,” Nhat Hanh often said.

Peace Advocate

Nhat Hanh traveled to the United States in 1961 to study at Princeton, and soon was appointed a lecturer of Buddhism at Columbia University. In 1963, he returned to Vietnam and continued to organize monks and lay people in non-violent peace efforts. He founded schools for activists, including the Van Hanh Buddhist University in Saigon, the La Boi publishing House, and inspired a generation of peace advocates with his essays, books, and poems written in Vietnamese, French, English and Chinese.

In 1966, Nhat Hanh returned to the U.S. and Europe with a mission; calling for the end to the hostilities in Vietnam. At that time he met Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The following year, Dr. King nominated Nhat Hanh for the Nobel Peace Prize, saying Nhat Hanh’s “ideas for peace, if applied, would build a monument to ecumenism, to world brotherhood, to humanity.”

While still in America, Nhat Hanh received messages from Buddhist leaders in Vietnam not to return for fear of assassination or imprisonment. Nhat Hanh began a life in exile that would last over four decades.

Life in Exile

Nhat Hanh moved to France, began teaching Buddhism at the University of Sorbonne, and initiated the Sweet Potato Buddhist community near Paris. The community later moved to the southwest of France and established Plum Village, which is one of the largest monasteries in the West with 200 resident monks and nuns, and where thousands of people from around the world come annually to study Nhat Hanh’s teachings on mindfulness and meditation. He later established monastic communities in Germany, Hong Kong, Thailand and America, as well as meditation centers around the world, gaining an ever-widening following.

The Dalai Lama has said of Nhat Hanh, “He shows us the connection between personal, inner peace, and peace on earth.”

In 2005 and 2007, Nhat Hanh was allowed to return to Vietnam to teach and publish books, tour the country, and meet with members of his Buddhist order. His highly publicized visits created controversy among some Vietnamese Buddhist activists who criticized Nhat Hanh for failing to speak out against the current governments alleged human rights abuses and poor record on religious freedom.

In 2018, after his brain hemorrhage, Nhat Hanh returned home to Vietnam to live at Tu Hieu Temple, where he had been ordained as a novice monk at sixteen years of age.

On Death and Dying

Nhat Hanh wrote and taught often about death and dying, and in his book, No Death, No Fear, he concludes, “This body is not me; I am not caught in this body, I am life without boundaries, I have never been born and I have never died. Over there the wide ocean and the sky with many galaxies All manifests from the basis of consciousness. Since beginningless time I have always been free. Birth and death are only a door through which we go in and out. Birth and death are only a game of hide-and-seek. So smile to me and take my hand and wave good-bye. Tomorrow we shall meet again or even before. We shall always be meeting again at the true source, always meeting again on the myriad paths of life.”

[/et_pb_accordion_item][et_pb_accordion_item title=”Linda Buckley” _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default” open=”off”]

I first met Thich Nhat Hanh in 1993. I had been studying Buddhism with other teachers but his teachings of “mindfulness in daily living” really resonated with me. After that week, I bought a bell and took his teachings into the classroom. I was teaching Alaska culture classes to high school students. When things got rowdy, I invited the bell and the students took three breaths. As months passed and we integrated the five steps of mindfulness into our lessons, the students would request the bell. “We need to breathe together.” And so we did.To say that Thay changed my life is an understatement. I attended other retreats with him and opened the Southeast Alaska Mindfulness Center in 1998 focusing on families. I was ordained by Thay in 1999.My last time with Thay was as a volunteer at a retreat at Deer Park Monastery in California. I will always remember walking with him and hundreds of others slowly in the sunshine. It was October and on his “continuation” day, or birthday I handed him a card. Placing two hands together at his heart he bowed.Later, in the garden of his personal residence, the volunteers were invited to share a meal with Thay. Someone asked me to sing. I sang a song by an Alaskan songwriter Libby Roderick.“How could anyone ever tell you, you were anything less than beautiful, how could anyone ever tell you, you were less than whole, how could anyone fail to notice that your loving is a miracle, how deeply you’re connected to my soul.”When I finished singing, there was a pause and then Thay began to wave his hands like dancing leaves, his way of clapping, and the monks and nuns did the same.by Linda BuckleyJuneau, Alaska

[/et_pb_accordion_item][et_pb_accordion_item title=”Shui Meng Ng” _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default” open=”off”]

Thay has left his body, he has not left us! That’s what we have learnt from him. Personally, I have learnt from him how to deal with loss and how to understand that what we have lost is not really lost. It’s still with us, in different manifestations. Any suffering of loss can be transformed into strength, courage, new understanding, and finally wisdom. For this I am forever thankful. But as Thay has taught – we need to practice and never give up on the practice for in practice is peace. Peace is every step.

Shui Meng Ng (wife of Sombath Somphone)

[/et_pb_accordion_item][et_pb_accordion_item title=”Theodore Mayer” _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default” open=”off”]

I would like to pay my respects to the recently departed teacher, Thich Nhat Hanh. I have

learned so much from him! But it began for me when I was just 17, and facing the possibility of

being drafted as a soldier to fight in Vietnam when I would turn 18 in a few months. I had just

graduated from high school, and I spent months living at my family's home, mostly reading, but

also volunteering as a draft counselor for other young men who faced the danger that I faced in

being drafted. (In all honesty, I found it difficult to be a draft counselor, which required listening

to men who did not want to fight in the war, while also trying to stay on top of the legal

ramifications and the options left open to them–jail, conscientious objection, fleeing to Canada,

or protest and living more or less underground–and how each one would work.)

Two small books made an enormous influence on my understanding of the war, and led to my

decision to never go to Vietnam as a US soldier. One of the books was Peace in Vietnam, by

the American Friends Service Committee of the Quakers. The other was the book entitled

Vietnam – Lotus in a Sea of Fire: A Buddhist Proposal for Peace. This book was written by Thich

Nhat Hanh, who also attended the Paris Peace Talks, and who met and exchanged views with

the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. (Martin Luther King was deeply radicalized in his view of US

foreign policy by Thich Nhat Hanh’s thought.)

As I read Thich Nhat Hanh’s book, I was overwhelmed with the sense that this man spoke from

a place of deep humanity and from a commitment to truth that had been shaped by his Zen

Buddhist tradition. He spoke persuasively about how the ordinary Vietnamese peasant viewed

the American soldier and the intensive bombing carried out by the US forces. It was refreshing

to finally have a Vietnamese voice presented to me, amidst the barrage of TV news and

pronouncements about why more bombing of Hanoi and gradually more and more places was

key to US national security. How wrong they were, and continue to be! Thich Nhat Hanh helped

me to realize even more deeply than I had before that I had to think for myself and always weigh

what political leaders said. For this and much more, I thank you, Thich Nhat Hanh.

[/et_pb_accordion_item][et_pb_accordion_item title=”Thi Tran Lahn” _builder_version=”4.8.2″ _module_preset=”default” open=”off”]

A poem in memory of Thich Nhat Hanh:

Short temporary living echoes forever.

Lighting up Plum Village for a thousand autumns.

Serenity in challenging; ups and downs

The mindfulness of peace and love spreads everywhere.

Thay return to the Stars.

I stay practicing your mindfulness of Peace and Love.

– Thi Tran Lahn

[/et_pb_accordion_item][/et_pb_accordion][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]