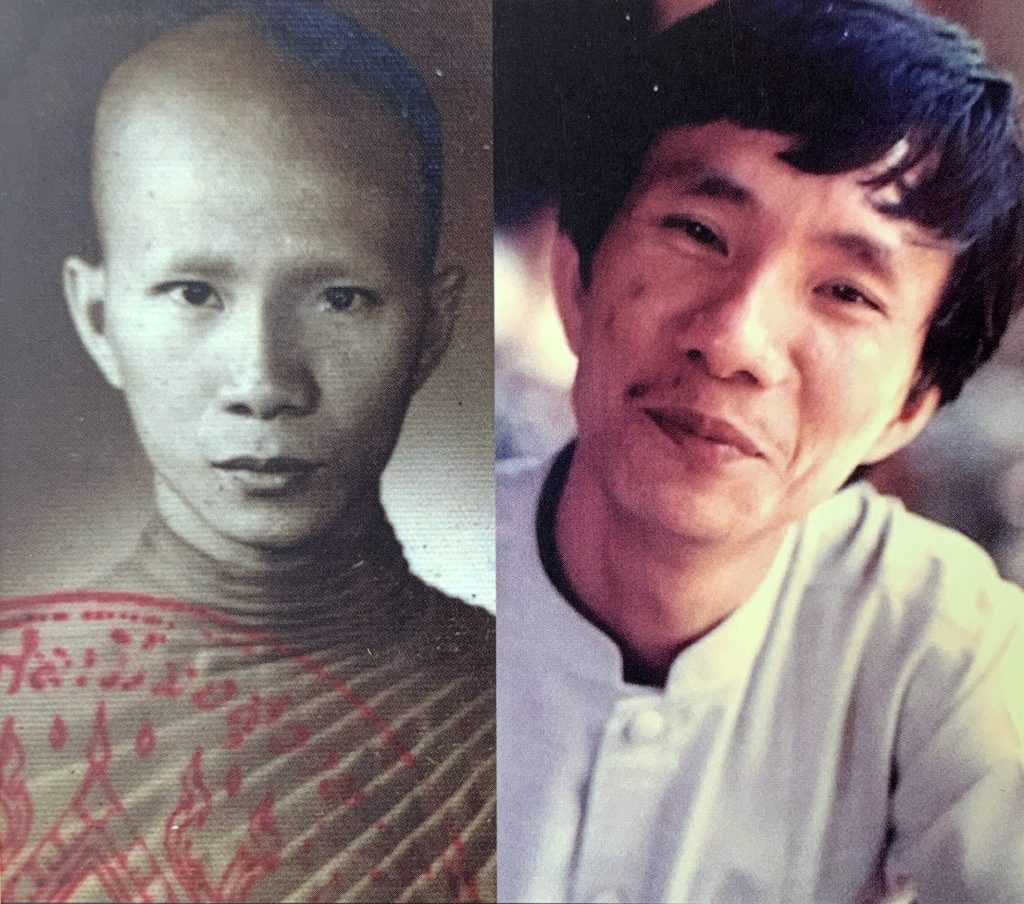

Background

Born on Friday 9 May 1952, Pracha grew up in a coconut plantation of Thonburi suburb which was later annexed as part of Bangkok.

Pracha’s family was Chinese overseas. His father, Mr. Chawhui Heng, worked a variety of jobs from running a warehouse of agricultural products in Tha Tian and Song Wat neighborhoods to earning his life as a fisherman on a ship, and being a Chinese language teacher. His paternal family settled in Tha Tian. His grandfather helped to bring overseas Chinese persons who travelled from China to become acclimated to life in Siam.

His mother was Somphon Chew. Her father, or Pracha’s grandfather, came from mainland China and spoke Teochiu just like his paternal family. His maternal grandfather earned his living making costumes for the Chinese Opera on Plaeng Nam Rd., China Town, while his maternal grandmother sold fruits and homemade Thai desserts at the Tha Tian market. Her famous desserts included mango sticky rice widely known as Mae Lek Tha Tian sticky rice.

Like many overseas Chinese families, Pracha’s father married before venturing to Siam, so did his mother. His mother and father met and married in Siam. Therefore, in terms of siblings, there were altogether nine since his father had a child from previous marriage, whereas his mother had one son and one daughter. Altogether in a new family, Mr. Hui and Ms. Somphon had five children together with Pracha being the third of the lineage.

All nine siblings, with only five who are still alive, include the following:

1. Mr. Chet Thanakulrangsarit (deceased)

2. Ms. Suraphee Fuangfung (deceased)

3. Dr. Narong Hutanuwatra

4. Ms. Somnoi Yuakyen (deceased)

5. Mr. Pracha Hutanuwatra (deceased)

6. Mr. Chatree Hutanuwatra

7. Mr. Prasat Kiatpaiboonkit

8. Mr. Chayadit Hutanuwachara

9. Ms. Somlak Hutanuwatra, the youngest female sibling

Pracha grew up in a family that lived from hand to mouth in a suburban home on a plantation with no electricity. He attended a nearby public primary school and later passed the entrance examination and enrolled in Suankularb School in grade seven. He was considered a rural boy who performed quite well academically.

The extreme poverty and the perseverance demonstrated by the parents made Pracha and other siblings realize the importance of weathering such a hard living since young ages. Such a predicament made each of the siblings super-tenacious, much more than an average child. This proved to be immensely useful for all of them later. It was a quality that helped them to succeed in anything they engaged with and how they devoted themselves to any cause with which they had the passion.

Since both parents were avid readers, even without electricity, they would light their home with oil lamps to read after the extremely tiring daily work and the multiple jobs they did. His father was a fan of the Siam Rath newspaper and listened every night to a radio program from Beijing via a shortwave radio. Perhaps, given such environment, Pracha naturally became an avid reader and always sustained his inquisitive mind. He even managed to build his own small hut under coconut trees not far from his house making it a library and a study just for himself. Many books were hoarded there and some have been passed on to his descendants.

A diligent and clever student, Pracha also cared for society since a young age. At Suankularb, he was engaged with various school activities being chairperson of the English Club, etc. He used to write and post a note to the school board when spotting anything wrong. Moreover, while in secondary school, he got together with fellow students from various schools to form “Yuwachon Siam” (The Young Siamese) including avant-garde students from many schools that did many activities together. They got together to exchange their ideas, to discuss, to read, to interpret and to debate. They organized rural camps for young people to live their lives in rural areas. It was during this time that Pracha studied the thoughts of Buddhadāsa Bhikkhu so keenly.

After completing high school and taking an entrance examination to enroll in university, given his academic excellence, Pracha could choose to enroll in any faculty. Eventually, he chose the Faculty of Education, Chulalongkorn University to follow the path of teacher Komol Keemthong, a trailblazer who devoted his life for others and society. After studying for more than a year, then came a political situation, which was the time when students questioned the meaning of their lives in the university enclave. It escalated to the 14 October 1973 Thai uprising event which prompted Pracha to drop out of Chula and embark on fierce fighting against the military dictators. Under these conditions, he was forced to change his lodging almost every night and could not return home. Given his sheer determination, Pracha eventually decided to devote his life to Buddhism, ahimsa and nonviolence through an ordination with key supporters including Sulak Sivaraksa and Buddhadāsa Bhikkhu of Suan Mokkh.

Being part of the Buddhist Sangha did not stop Pracha from being engaged with society. He continued to work for society while practicing his contemplative life just as he proposed this way of life in his book Contemplative Life and Social Engagement. While ordained as a Ven. Pracha Pasannathammo, he was invited to give a keynote lecture for the Komol Keemthong Foundation in 1981. This helped his social engagement to be even more deeply entrenched, and it differentiated him from other activists since he never dismissed his spiritual wellbeing and self-development. Capitalizing on his social engagement and contemplative life, Pracha expressed his ideology through his translation works, his writing, training and organizing various organizations, as well as his travel in Thailand and abroad. By traveling he made an immense contribution to young people’s development in other countries throughout Southeast Asia, in Burma, Laos and Cambodia, and even mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, USA, UK and other countries in Europe.

Pracha devoted the last three decades of his life to develop socially engaged Buddhism and related work inside and outside Thailand, for example:

- In 1989, Pracha, his friends and his mentor, Sulak Sivaraksa, helped to found the International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB) to coordinate among Buddhist activists and leaderships from other religions and countries to organize an exchange and to help each other in their social engagement.

- Pracha was invited to participate in the advanced course of Training of Trainer by A Movement for Society in Philadelphia, USA. He used the experience to organize groups and launched training courses in Thailand. Its curriculum was developed to cater to the Buddhist context. Eventually, he developed his own training project called the Grassroots Leadership Training (GLT).

- The Wongsanit Ashram in Klong 15, Nakhon Nayok, is an alternative community which has been developed with much help from Pracha. It serves as a space for social activists to experiment with their living on a 12 acre piece of land donated by MR Saisvasti Svastivatana to Sulak Sivaraksa and the Sathirakoses Nagapradipa Foundation for public interest. It was meant to be an alternative community by living simply close to nature and use contemplation as a basis for activism and social change. It provides an opportunity for community members to learn and explore their own potential. It is a place for healing to restore the balance of life. It was a breeding ground for score of social activists, Thai and foreign, who have expanded their work in various parts of society.

- With his incessant inquisitive mind, Pracha has travelled the world to participate in various courses which he found may help to achieve a just society, He also wanted to apply such training courses to cater to education in Thailand that were based on Buddhist teachings and humanity. Particularly during his time at the Findhorn Foundation in Scotland, Pracha helped to design the Ecovillage Designed Education (EDE) curriculum which integrated the discourses on economy, society, cultural, education and the environment together to create a learning process to engender a decent and just society.

- With his interest in alternative education, Pracha founded the Yuwa Buddhichon Institute to epitomize Buddhadāsa Bhikkhu’s belief that “Morals of youth are peace of the world.” It offers training courses for youth and people who work with children and youth. It provides an educational environment in which the participants are encouraged to develop creative approaches to education to acquire knowledge and to ensure such education can bring about social transformation eventually.

- For business people and politicians, Pracha helped to found the Right Livelihood Foundation which may not reach its ideals, but has contributed immensely to society.

- In addition, he attempted to found the Ecovillage Transition Asia which focusses on the transformation to a livable city that would offer an education to ordinary people in urban areas and encourages people to farm in the city. This was inspired by the idea of transforming relationships between humans and nature to ensure sustainable ecology. Even though this is a low profile project, he personally contributed to it.

- Pracha always focused on social transformation through valuing change among people in society. Therefore, toward the end of his life, he developed the Awakening Leadership Training (ALT), conducted in Thai and English, to help organize groups of students, dreamers and practitioners here and abroad to come to terms with leadership in modern society and the new paradigms that true leaders have to be internally stable, awakened and humble.

- Lately, Pracha devoted himself to developing the SEM Publishing House to disseminate good information to people in society. Some publications are intended as reading materials for ALT participants so that they can learn the kind of knowledge shunned by most textbooks.

This is part of the work Pracha had been mainly engaged with.

It is also good to get a glimpse of Pracha family life. It is good to harken back to stories about Pracha, his mother and his family, his life during ordination as a Buddhist monk who was so keen on practicing the Dhamma.

Apart from the benefit felt by himself and society, his 12 years in monkhood was also a tremendous blessing for his family members, particularly his mother. She had been practicing Daoist meditation for a long-time and had since acquired deeper understanding about Buddhism. Later in her life, she was ordained as a nun at Suan Mokkh practicing and studying Dhamma of the Buddhadāsa Bhikkhu’s school for one year under the close guidance of Ven. Pracha. According to Buddhism, one of the best ways to express gratitude to our parents is to help them become enlightened and practice the right kind of Dhamma as well as progressively cleanse their mind. Based on this, Pracha has done his best as a son. More concretely, he even reminded his mother that death could happen anytime by constantly asking her “Mom, do you fear death?” This served as a mantra for his siblings to keep reminding her during her final hours and to stay close to her as much as they could.

Once, his mom needed an emergency operation when she was nearly 80. His younger sibling who took care of her asked her while she was on bed and being pushed into the operating theater “Mom, do you fear death?,” and she replied “I don’t.” After several hours of intense waiting, the nurses pushed her out of the operating theater. Taking a glance at her children, she declared in feeble voice “I am not dead yet” yielding such an outburst of laughter from everyone.

This could be said to be a Dhamma heritage, the spiritual refuge for the family left by Ven. Pracha.

Another story also reflected a character of Pracha. When his mother retired herself from such hardworking life and moved away from the bustling atmosphere, every time when Ven. Pracha came to visit her, he brought an audio recorder to record his conversation with his mother. Pracha asked many questions for her to recount many interesting stories from the past. He collected several cassette tapes, because he intended to write and publish a memoir of his mother since for him, she was a trailblazer and a rebel who was so inspiring. Many attested to her character when she raised her fists amidst a thousand of people inside the main auditorium of Thammasat University while shouting “My son was not wrong.” This took place when Chatree, Pracha’s younger brother who was a student of medicine from Chiang Mai University, was convicted and sentenced to jail for supporting the peasant uprising. For Pracha, his mom was an ideal model for a rebellious life, someone who always fought for justice. Unfortunately, Pracha’s life was cut short, and devoted himself to many other social causes, until he could not accomplish what he wanted to do for his family.

Pracha married Jane Rasbash after meeting at a Deep Ecology Summer School in California in 1994. Jane moved to live at the Wongsanit Ashram where she assisted Pracha and Ajarn Sulak organize the Alternative to Consumerism Conference at Buddhamandala Park near Bangkok in 1996. At the same time Pracha and jane initiated the Grassroots Leadership Training for People from Burma. Later on, they settled in Scotland at the Findhorn Ecovillage Community. They continued to work together, write together, provide training together and support each other for years before and after their marriage ended.

In his later life, Pracha moved to a Bangkok suburb of Sai Mai area where he lived in a two-story wooden house made of wood dissembled from the previous house given to him by his older brother and his mother. The ground floor is teemed with warm earth, lushed with bamboo groves and other plants, not dissimilar to his old home in Thonburi, and as always littered with many books.

Pracha is survived by his only son, Namo Chettanaweerabut Hutanuwatra, and his wife, Chofa. Both Namo and Chofa have been contributing immensely to Pracha’s cause.

Late morning on 13 May 2023, Pracha Hutanuwatra passed peacefully while saying a prayer and counting beads and on a piece of Khata at the Siriraj Hospital.

It could be summed up that “Pracha” lived the life of a social revolutionary who never hesitated to devote his whole life to his dream causes. He devoted his life to prove the truth. He lived a rebellious life not bound by any tradition. His passion was to help people to be intellectually free from any narrow mindset and values, and dare to choose the life they wanted. He always envisaged a just society and a justice system that genuinely serves as a pillar of society. Pracha believed that by helping people or giving them a chance to discover their good nature, it will give rise to their discovery of power which can help to bring about social change from each person eventually.

As of now, we believe the rebel spirit of Pracha has a chance to rest in peace somewhere in another realm.